The History of Python DataFrame Libraries

Where We Stand in 2026

Pre-DataFrames

If you open Python in 2007 and try to work with data, you don’t see tables. You see lists. Dictionaries. Loops. You might load a CSV file, but then you manually index into rows, convert strings to numbers, and write for-loops to compute totals. It works, but it feels mechanical. There is no shared structure for tabular data.

Pandas

In 2008, that changed. Pandas introduced the DataFrame.

A DataFrame is simply a table in memory. Rows and columns. Like Excel. Like SQL. But inside Python.

You can create one from a CSV file with a single line:

import pandas as pddf = pd.read_csv("sales.csv")

Suddenly, df is not just a list. It has columns. You can access them directly:

df["revenue"]

That returns a column. You can filter rows:

df[df["revenue"] > 1000]

You can group and aggregate:

df.groupby("region")["revenue"].sum()

This syntax is expressive. You describe what you want, not how to loop through rows. For millions of analysts, this became the default mental model of working with data in Python.

Even now, pandas is still the most widely used DataFrame library. It dominates education, notebooks, quick analysis, and mid-sized workloads. But it assumes something critical: your data fits into memory. The DataFrame lives in RAM. When it grows too large, you hit limits.

PySpark

In 2009, Spark took the DataFrame idea and moved it to clusters. With PySpark, you could write code that looks similar:

from pyspark.sql import SparkSessionspark = SparkSession.builder.getOrCreate()df = spark.read.csv("sales.csv", header=True)

The syntax feels familiar. You can filter:

df.filter(df.revenue > 1000)

You can group:

df.groupBy("region").sum("revenue")

But the difference is architectural. Spark DataFrames are lazy. When you write transformations, nothing runs immediately. Spark builds a query plan. Only when you call an action like .collect() does computation happen, distributed across machines.

This allowed terabytes of data to be processed. Spark is still heavily used in enterprises, especially in Databricks environments. But it is infrastructure-heavy. Clusters, orchestration, cost management. Powerful, but not lightweight.

Dask

In 2014, Dask tried to scale pandas without requiring full Spark infrastructure. The syntax looked almost identical to pandas:

import dask.dataframe as dddf = dd.read_csv("sales.csv")

You still use groupby, filter, and column operations. Under the hood, Dask partitions the DataFrame and distributes work across cores or machines. It feels like pandas, but execution becomes parallel. Dask remains important in scientific computing and custom distributed Python systems, though it never overtook Spark in mainstream enterprise use.

Vaex

That same year, Vaex approached the problem differently. Instead of distributing across clusters, it optimized memory usage using memory mapping and C++. You could work with billion-row datasets on a laptop because Vaex avoided copying data into RAM unnecessarily. Its syntax resembled pandas, but it emphasized lazy operations and efficient computation. Vaex never became dominant, but it influenced the broader move toward Arrow and columnar memory.

Ibis

In 2015, Ibis introduced a radically different idea. Instead of executing computations in Python, Ibis builds an expression tree and compiles it to SQL. The syntax looks Pythonic:

import ibist = ibis.table([("revenue", "float"), ("region", "string")], name="sales")result = t.group_by("region").aggregate(total=t.revenue.sum())

But nothing runs in Python memory until you collect the result. Ibis translates this into SQL and pushes it to a backend like DuckDB, Snowflake, or BigQuery. Ibis has become highly relevant in modern data engineering. It allows you to write DataFrame-like code that runs inside databases, combining portability with performance.

cuDF

In 2017, GPUs entered the picture with cuDF. The syntax mimics pandas almost exactly:

import cudfdf = cudf.read_csv("sales.csv")

You still filter and group the same way. But the computation happens on a GPU, enabling massive parallelism. cuDF is powerful in machine learning pipelines and NVIDIA-heavy environments, but it remains specialized.

Between 2018 and 2019, we saw a convergence around the pandas API. Modin promised that you could “change one import” and scale pandas across Ray or Dask. Koalas, later renamed pandas API on Spark, brought pandas-style syntax directly to Spark clusters.

Polars

Then, in 2020, Polars arrived and changed the momentum. Written in Rust and built around Apache Arrow, Polars introduced a modern execution engine. It supports both eager and lazy modes. The syntax feels familiar but more explicit:

import polars as pldf = pl.read_csv("sales.csv")df.filter(pl.col("revenue") > 1000)df.group_by("region").agg(pl.col("revenue").sum())

Polars expressions are column-oriented and composable. When used in lazy mode, it builds an optimized query plan similar to Spark, but executes efficiently on a single machine using multithreading. Polars has become mainstream among performance-focused data engineers. Pandas still wins on total usage, but Polars wins on performance credibility and technical momentum.

Snowpark Python

In 2022, cloud warehouses embraced the DataFrame interface. Snowpark Python allowed users to write DataFrame code that runs inside Snowflake:

df = session.table("sales")df.filter(df["revenue"] > 1000)

Execution is pushed entirely into the warehouse. Similarly, BigQuery introduced DataFrame-style interfaces. This pattern is increasingly common in enterprises. The DataFrame becomes an API layer over cloud compute.

Newer Entrants

Newer entrants like Daft and DataFusion build on Rust and Arrow foundations, blending distributed execution with modern memory models. SQLFrame provides a backend-agnostic DataFrame API that compiles to SQL engines. The ecosystem continues to evolve.

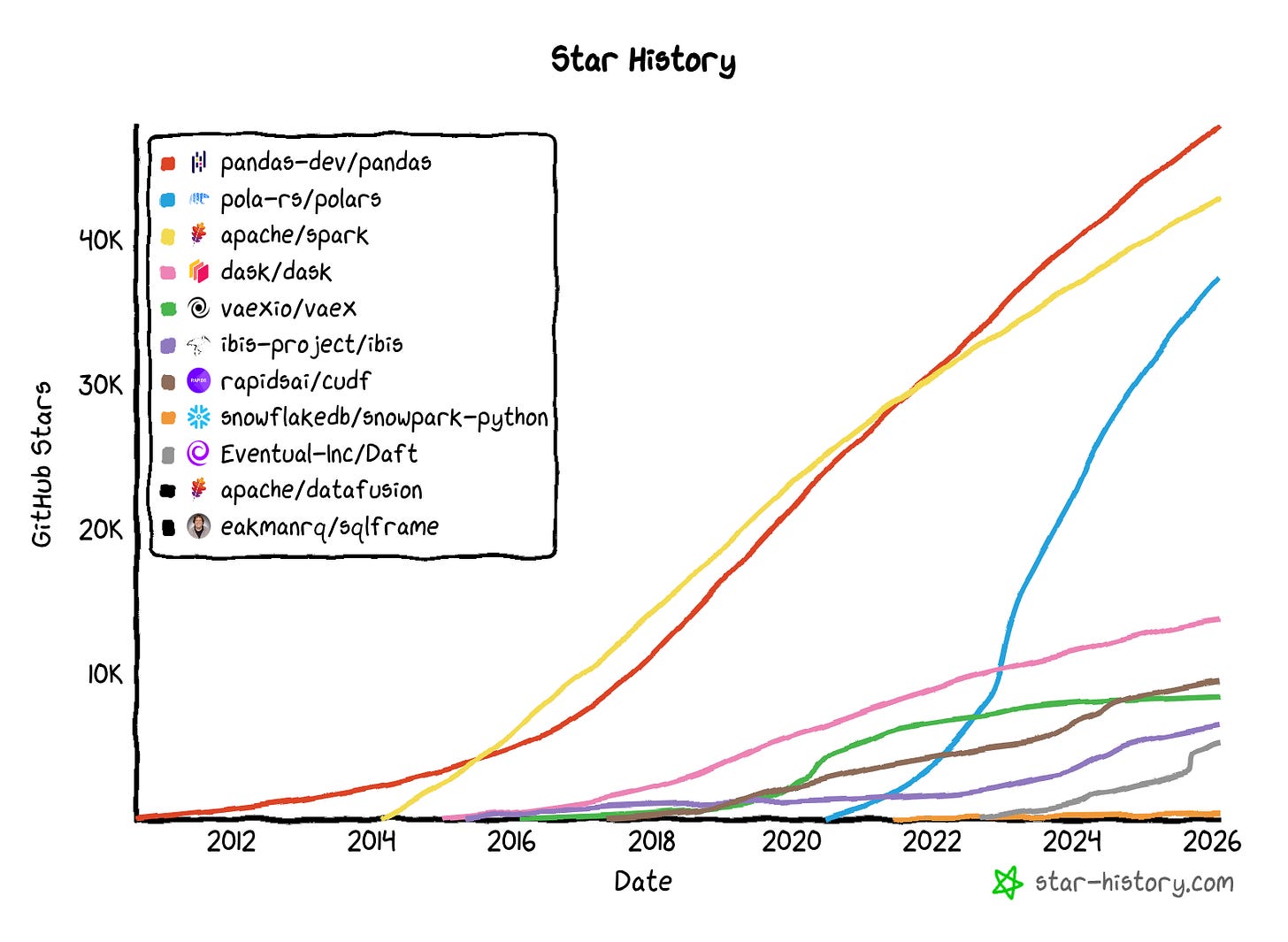

GitHub Star History

Pandas remains the most popular dataframe library due to its first-mover-advantage.

Polars and PySpark are catching up, likely due to the performance gains and improved syntax compared to Pandas.

The rest of the libraries have niche use cases (with ibis being one of my favorites).

Choosing a DataFrame Library

If your data is in local files (CSV, Parquet, JSON, Excel)

Small and fits in memory → pandas

Simple

Beginner-friendly

Most tutorials use it

Large but still on one machine → Polars

Fast

Uses all CPU cores

Great for millions of rows

Extremely large and requires multiple machines → PySpark

Built for clusters

Handles very large datasets

If your data is in a database or warehouse (Snowflake, BigQuery, Postgres, DuckDB)

Small or large → Ibis

Write Python

Executes as SQL inside the database

Keeps computation close to the data

Distributed at scale → Ibis or PySpark

Depends on your infrastructure

Spark if you already operate clusters

If you use Snowflake → Snowpark Python

If your data is in a distributed system or data lake

Designed for multi-machine compute → PySpark

Built for distributed processing

Common in enterprise data platforms

Summary

A DataFrame is a table abstraction. You load data into it, refer to columns by name, filter rows based on conditions, group by categories, and compute aggregations. The syntax generally follows a pattern:

Select columns.

Filter rows.

Group and aggregate.

Join tables.

Whether you are using pandas, Polars, Spark, Ibis, or Snowpark, those operations look conceptually similar. What changes is where and how computation happens: in memory, across cores, on clusters, on GPUs, or inside databases.

The DataFrame began as an in-memory convenience. Now, it is a universal abstraction across compute engines. The API feels simple. The engines underneath are not.